by D. Movieman

“I’ll love you until the umiak flies into the darkness, till the stars turn to fish in the sky,

and the puffin howls at the moon.”

— Mama, Do You Love Me? by Barbara M. Joosse

Before I ever traveled the world as a young adult, I saw the world through the eyes of

children’s literature. “Mama, Do You Love Me?” was just one selection in a vast literary

universe of cultures, myths, and imagination. I will always have my grandmother Nani to

thank for that—a woman with a Master’s +30 and a passport full of stories, who poured

her knowledge into her two-year-old grandson, already teaching himself to read.

Barbara M. Joosse’s book was not a definitive portrait of Arctic Inuit culture, but it

offered an early foundation that would grow with time. Most importantly, it helped me

understand that, whether in the icy winters of the Midwest or the Arctic homelands of the

Inuit, love is—when genuinely given—pure and limitless.

Such a love forms the emotional core of Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband), set 4,000

years ago in the Canadian Arctic. At its center are Kaujak (Theresia Kappianaq) and

Sapa (Haiden Angutimarik), a pair promised to each other from birth. When an

unforeseen tragedy separates them, a shaman’s guidance and the intervention of Inuit

deities set their path toward reconciliation. Given my aforementioned experiences,

there’s always a special love I have for stories set in the past, as well as those that

distinctly capture non-American cultures. Who better, then, to showcase a story like this

than director Zacharias Kunuk?

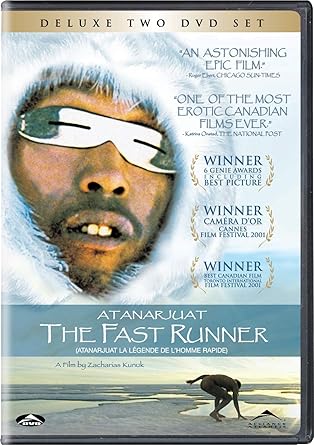

This Canadian Inuk producer and director is most known for his

2001 feature debut Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. It went on to make history as the first

Canadian dramatic feature film to be written, directed, and acted entirely in the Inuktitut

language.

A similar devotion to preservation permeates the world of Uiksaringitara, ensuring that

Inuit voices, language, and traditions are still centered in the cinematic landscape over

two decades later. On the subject of landscape, the film excels most at its visual

capturing of Igloolik, as seen through its frozen expanses and vast horizons. Beyond its

characters or story, the film actively pays tribute to the land that the Inuit populate.

An evident example is a scene where two women converse happily while lying on the

ground, watching a boundless sky as they sample some of the sprouts they’ve just

collected. The scene itself is simple, but its purpose is far more profound.

Although the performances—like the film itself—are far more subdued, Theresia

Kappianaq is the clear standout. She brings Kaujak to life with a subdued intensity and

open vulnerability that drives the film forward. For me, her strongest moment comes

when she cries helplessly to a rising moon, lamenting her tragic circumstances while

asking her promised husband to find and save her. She is unaware, of course, that her

cries have not gone unheard. Emma Quassa’s turn as the stoic, but divinely attuned

Ulluriaq is equally memorable.

My one central disconnect with the film comes with its stilted pacing and interweaving of

story elements, particularly with the emphasis placed on the supernatural. In its opening

scene, Uiksaringitara wastes no time establishing that this environment holds

dangers—seen and unseen. In the vein of the timeless story, The Illiad, divine figures

from the Inuit world make their presence known, steering the course of Kaujak, Sapa,

and their families’ lives. This element is visually dynamic, but plot-wise, it feels oddly

disconnected. One half of the film feels like a showcase for the habits and general

experiences of its villagers as they go about their lives, almost akin to a docuseries. On

the other hand, the supernatural element of the film almost feels like another story

entirely—one that functions as an intriguing detour into a world that is never fully

explored or fleshed out. Together, they make for a tonal and narrative dissonance that

makes for a disjointed viewing experience.

Ultimately, Uiksaringitara, like Zacharias Kunuk’s previous works, functions as a love

letter to the legacy and lives of the Inuit. However, viewers hoping for a more standard

film experience may find themselves struggling to break the ice.

Rating – 7/10.