It’s been more than three decades since Mexican actress Salma Hayek left her native country to start a successful film career in Hollywood, beginning with her breakthrough role in Robert Rodriguez’s Desperado (1995).

That same year, she starred in one of the few Mexican productions of the late 20th century to achieve box office success: Jorge Fons’ El Callejón de los Milagros. This was notable given that the Mexican film industry would soon collapse to producing just 10 films in 1997—decades after the so-called “Golden Age of Mexican Cinema,” which peaked in the late 1930s with Fernando de Fuentes’ Allá en el Rancho Grande and continued through the 1950s with Revolutionary epics such as Ismael Rodríguez’s La Cucaracha (1959), starring Mexican diva Dolores Del Río.

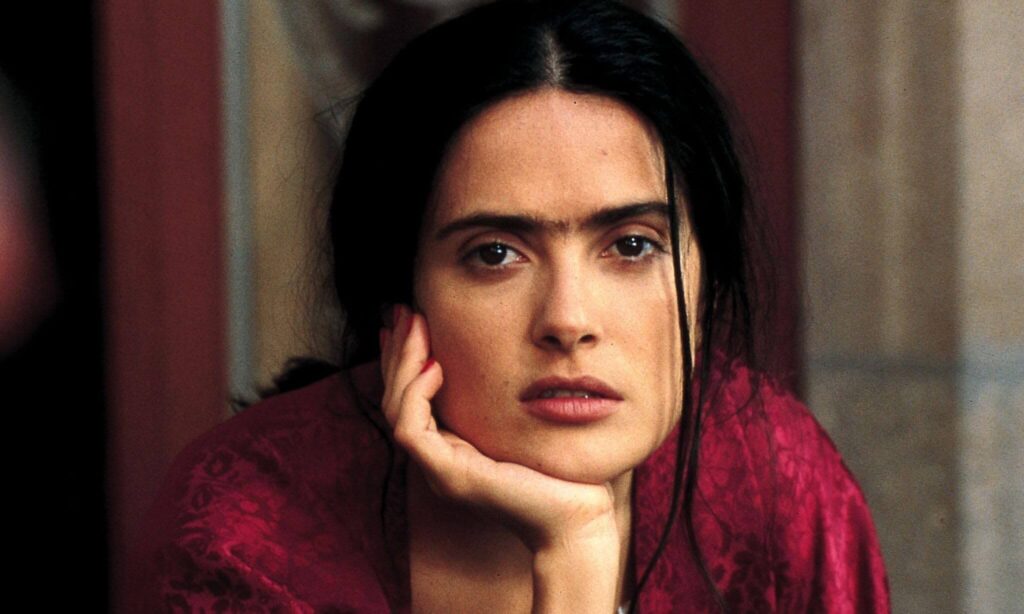

Unlike Del Río, who returned to Mexico after becoming a pioneering Hollywood star, Hayek has rarely revisited her homeland since achieving stardom. On her visits, such as in the early 2000s to promote her Academy Award–starring and producing biopic Frida (2002), she even reported incidents like a journalist hitting her with a microphone while chasing her for a comment.

The experiences of Del Río and Hayek reflect the vast cultural and political differences between their respective eras. Del Río navigated the machismo of 20th-century Mexican directors such as Emilio “Indio” Fernández, as well as oppressive regimes including President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (1964–1970), who oversaw the Tlatelolco Massacre in 1968. Despite these challenges, she became a cultural icon, openly critiqued the raw realism of “New Mexican Cinema” in the 1970s, and supported the growth of Mexico’s film institutions.

Hayek, in contrast, has benefited from supportive government figures since Frida. Presidents Vicente Fox (2000–2006) and Felipe Calderón (2006–2012) backed projects such as Once Upon a Time in Mexico (Robert Rodriguez, 2003) and Bandidas (Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg, 2006), and helped establish tax incentives like EFICINE, designed to boost the Mexican film industry following Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Amores Perros (2000).

On February 15, 2026, Hayek returned to Veracruz to join President Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo—the first female president of Mexico—to unveil incentives supporting local cinema and attracting international productions. Hayek praised Sheinbaum as a “different kind of treatment, having a woman in power, unlike former presidents who were difficult and barely supportive.”

However, Hayek’s comments sparked criticism. Social media and traditional outlets reminded her that previous administrations, including those of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018–2024) and Sheinbaum (2024–2030), had eliminated important film support structures, such as FIDECINE in 2020. Critics argued that Hayek, married to one of the wealthiest men in the world and living abroad, seemed detached from the realities of her home country.

Dolores del Río, by contrast, retired with honor after her last film, Children of Sánchez (Hal Bartlett, 1978), leaving a legacy that included cultural initiatives such as the Guanajuato International Cervantino Festival and programs for children in Mexico City. Salma Hayek now faces her own place in Mexico’s cinematic and cultural history, balancing advocacy, celebrity, and the realities of film policy—especially as international players like Netflix continue to invest in the country.